(Op-ed in response to Minister Groenewald’s call to “debate” the return of corporal punishment).

Minister Pieter Groenewald’s suggestion that South Africa might curb overcrowded prisons by re-legalising corporal punishment lands like a museum piece dragged into a policy debate.

The wit is that we have, in fact, tried both the cane and mass incarceration before – and neither has made us safer. The data says our real blind spot may be medical, not medieval: an epidemic of undiagnosed neurodivergence, especially ADHD, running through our justice system.

It’s unconstitutional – and internationally verboten

The Constitutional Court outlawed judicial whippings thirty years ago in S v Williams (1995) for breaching the right to dignity and freedom from cruel, inhuman or degrading punishment saflii.org.

Parliament followed with the Abolition of Corporal Punishment Act (1997). Re-booting the practice would need a two-thirds constitutional amendment – only to collide with the UN Mandela Rules, which list corporal punishment alongside torture as absolutely prohibited (Rule 43 1(d)) solitaryconfinement.org.

Corporal discipline does not shrink prison queues

Groenewald’s complaint is that ±2 500 remand detainees cannot raise R1 000 bail.

Hitting them once and releasing them would leave intact the real bottlenecks: clogged courts, unaffordable bail, and a pipeline of repeat offenders whose root problems are untreated.

Evidence is consistent that harsh physical penalties provide a short-lived deterrent and can increase later violence, especially among trauma-exposed offenders.

A root cause we keep missing: untreated ADHD

A recent meta-analysis of 102 studies (69 997 participants) found 26 % of adult prisoners and 30 % of youth meet diagnostic criteria for ADHD – roughly ten times community rates pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

South Africa has never formally measured this, but if prevalence mirrors global figures, 30 000–40 000 inmates could be living with ADHD today, almost none diagnosed during intake exams.

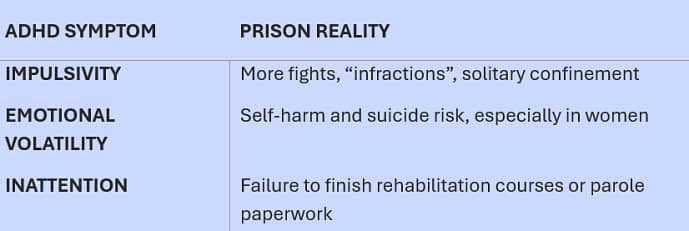

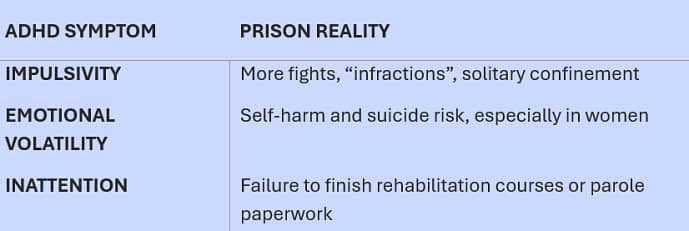

What untreated ADHD looks like behind bars:

A UK parliamentary submission put the price tag at £590 extra per ADHD inmate per year in disciplinary costs and healthcare; that scales to millions of rand in South Africa’s already-thin corrections budget.

Treatment works – and pays for itself

A landmark Swedish registry study tracked 25 656 diagnosed adults and found 32 % (men) to 41 % (women) fewer criminal convictions while on ADHD medication nejm.org.

In other words, pharmacological treatment cuts recidivism by about a third – results solitary confinement or lashes have never achieved. Even non-pharmacological programmes (CBT for impulse control, structured skills training) improve behaviour and reduce prison incidents.

Policy triage: what would cut numbers fast?

Screen on intake with a six-item ADHD checklist; flag positives for assessment.

Allow controlled stimulant or non-stimulant medication under supervised dispensing – the same security already used for antipsychotics or opioid substitution.

Train wardens: a two-hour neurodiversity module costs less than one riot.

Divert low-risk neurodivergent offenders to community treatment instead of short jail terms where possible.

Automate bail reviews for minor offences; the real cost driver is remand detention for poverty crimes, not sentencing leniency.

A smarter politics of safety

Re-introducing the cane would burn political capital, trigger certain litigation, and still leave prisons stuffed with neurodivergent South Africans who bounce out untreated and back in again.

Addressing ADHD and other invisible disabilities, by contrast, attacks re-offending at its neurological roots and aligns with constitutional and international obligations.

South Africa has an opportunity: become the first African country to pilot routine neurodevelopmental screening in prisons and measure the downstream impact on violent incidents and repeat crime.

The technology is cheap, the medications are off-patent, and the savings – fiscal and human – are real.

Download the evidence pack – a concise briefing with sources, prevalence numbers and policy recommendations: ADHD & Incarceration Summary (2020-2025).

Key take-aways

Corporal punishment is constitutionally dead and globally banned.

Upwards of a quarter of inmates likely have ADHD; almost none treated.

Medication and targeted programmes cut recidivism by up to 40 %.

Screening, treatment and bail reform deliver bigger, legal reductions in overcrowding than any cane.

Next step: will Parliament debate evidence-based reform – or spend time resuscitating punishments the Constitution buried in 1995?